| Status | Legacy |

| Launch | 1975 |

| Space organisation | ESA |

| Type | Gamma rays (0,25 – 25 fm / 50 MeV-5 GeV) |

| Orbit | Elliptical geocentric |

| SRON contribution | Anticoincidence Counter |

In the 1970s, gamma-ray astronomy was still in its infancy. Gamma rays form the most energetic radiation in the Universe and is produced by celestial phenomena such as supernova explosions and the interaction of cosmic rays with interstellar gas.

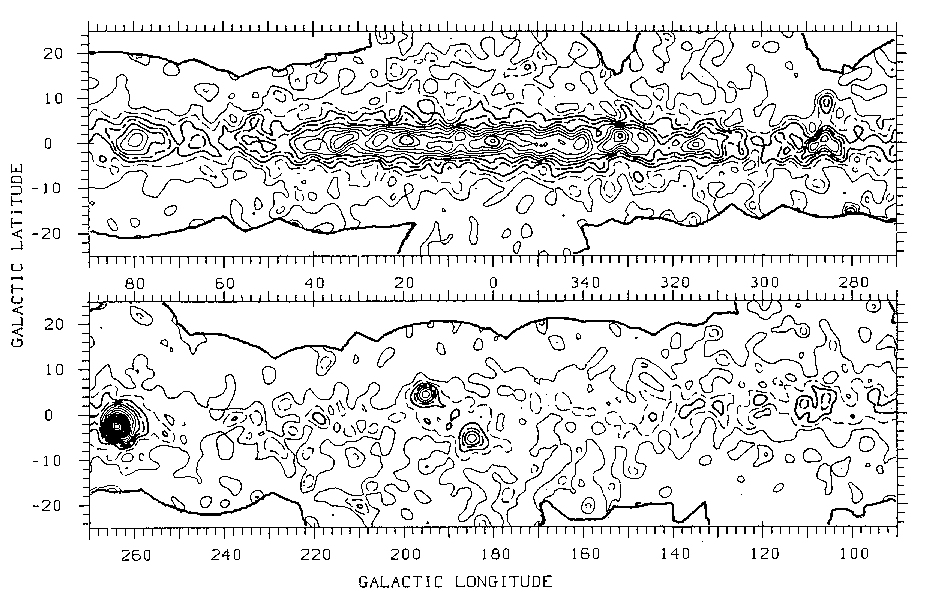

Mapping the Milky Way

COS-B produced the first map of the Milky Way in gamma rays that revealed not just a diffuse glow, but also a resolved structure. This map confirmed that cosmic rays interact with hydrogen gas in the disk of our galaxy. Consequently, COS-B was also able to distinguish individual stars — specifically pulsars — from the Milky Way’s background radiation. For example, the Vela and Crab pulsars appeared on the map as distinct hotspots. This provided proof that gamma rays originated not only from diffuse gas, but also from specific compact objects.

Radio-quiet Pulsars

Additionally, COS-B stumbled upon a major mystery: a bright source of gamma radiation named ‘Geminga’, which was invisible in optical light and radio waves. This ultimately led to the discovery of a new class of objects: radio-quiet pulsars. These are rapidly rotating neutron stars that are visible almost exclusively in X-rays and gamma rays.

Quasars

Finally, COS-B looked beyond our own Milky Way. The satellite detected the first source of gamma radiation from outside our galaxy: the quasar 3C 273. This demonstrated that bright galaxies also emit enormous amounts of high-energy radiation into space. It proved that gamma radiation is not limited to our local environment, but is a universal phenomenon in the cosmos.

Gamma rays cannot be captured with mirrors or lenses; the radiation is so powerful that it passes straight through matter. To measure them anyway, COS-B’s telescope consisted of a spark chamber. When a gamma-ray photon entered the chamber, it triggered a chain reaction that left a trail of sparks.

However, there was a major problem: space is filled with cosmic rays. Contrary to what the name suggests, these consist of charged particles, primarily protons. For every gamma photon COS-B wanted to capture, thousands of protons flew through the satellite, producing sparks in the detector just like gamma rays. Without a filter, COS-B would produce a map filled with false detections.

SRON’s Contribution

To filter out this chaos, SRON developed and built the Anticoincidence Counter (ACO). This was a dome that completely enclosed the spark chamber. The system made use of the physical difference between cosmic rays, which are electrically charged, and neutral gamma radiation.

When a charged particle hit the dome, the plastic would briefly light up. The electronics then knew to ignore this specific measurement. Gamma rays, on the other hand, passed through the dome unnoticed, only reacting once they reached the spark chamber.

Image caption:

The first map of the Milky Way in gamma rays (150–300 MeV). Previously, it was visible only as a diffuse glow. Top: COS-B centered on the Galactic Center. Bottom: COS-B centered on the Galactic Anticenter. The Vela pulsar is clearly visible near l ~ 263 and the Crab pulsar near l ~ 184. The mysterious Geminga pulsar can be seen near l ~ 194. Credit: ESA