Billions of galaxies

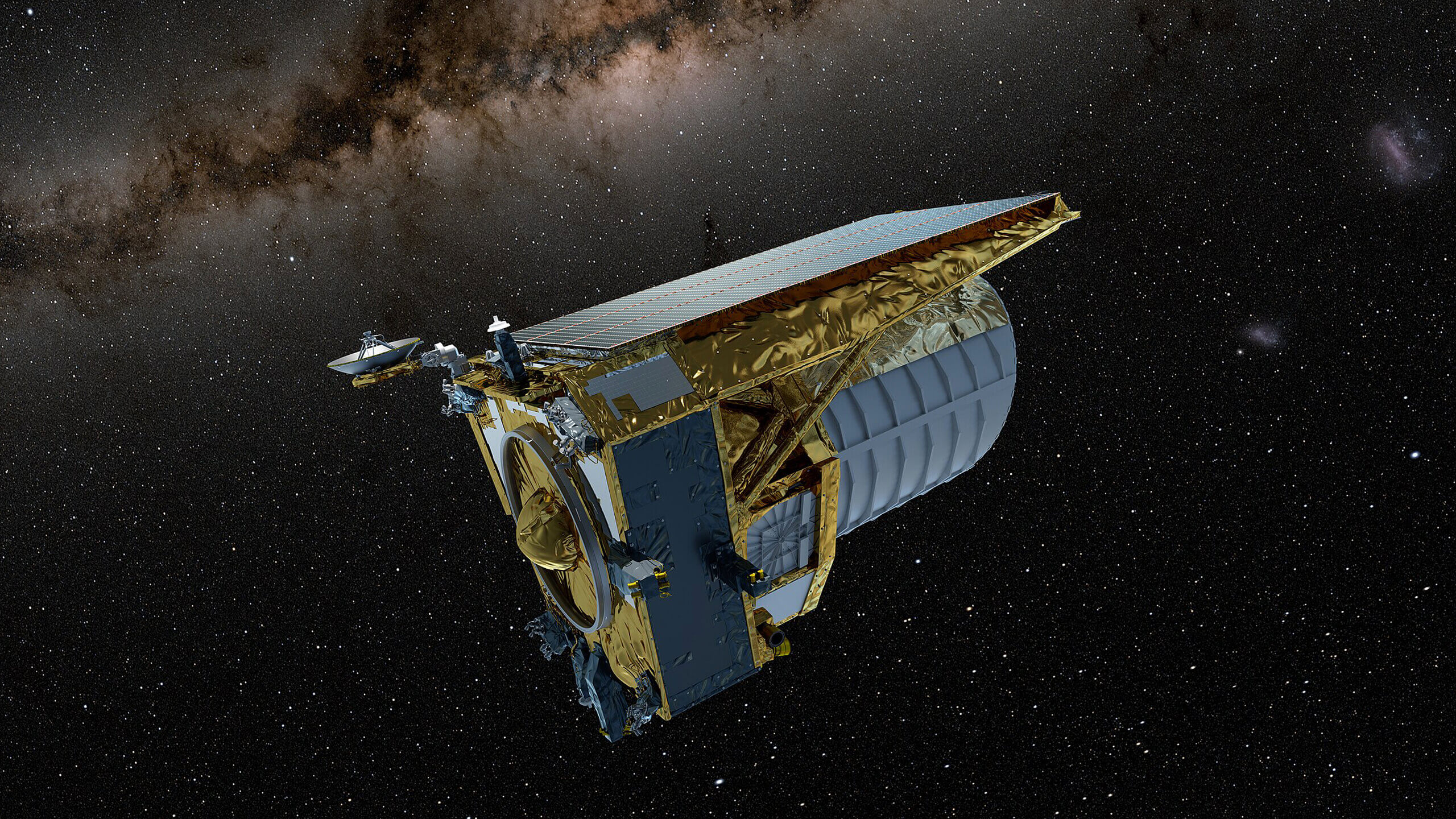

Euclid maps out in 3D billions of galaxies across an area covering approximately a third of the sky. Its wide spectroscopic survey will reach a limit of roughly 10 billion light years. This gives us the number of galaxies that formed at a given time in the Universe. And the speed at which each galaxy is moving away from us tells astronomers how fast space is expanding at that point in the Universe.

SRON researchers are using Euclid’s large database to look for connections between the presence of active galactic nuclei (AGN) and galaxy mergers, i.e. collisions between two or more galaxies). Using a large sample of millions of galaxies, they have demonstrated that mergers play a significant role in triggering the supermassive black holes at the centres of galaxies. In the case of the brightest AGN, a merger is even the main and possibly sole trigger for them to start shining.

Dark energy

The Universe has been expanding ever since the Big Bang. You might expect that gravity slows everything down and eventually brings it all back together. However, since the 1990s we have known that the expansion is accelerating rather than slowing down. Astronomers have coined the term ‘dark energy’ for the mysterious force behind this. According to the ‘standard model of cosmology’, every given volume of space contains a fixed amount of dark energy. As more space is continuously added to the Universe, more and more dark energy has been accumulating since the Big Bang. Eventually, the expanding force of dark energy prevailed over the contracting force of gravity. That tipping point occurred nine billion years after the Big Bang.

Euclid is investigating whether this standard model is correct, or whether dark energy is variable per volume of space. Thanks to its enormous database of galaxies, Euclid can divide the Universe into small time periods, each with its own expansion rate. All these frames form a film of the history of the expansion of the Universe. The number of galaxies that could form within each frame tells us something about the attractive force of gravity versus the expanding force of dark energy. If that ratio differs from our expectation at certain points in time, it would suggest that dark energy is not just a plain sum of volumes of space, as the standard model proposes.

Dark matter

The speed at which galaxies spin has been a mystery to astronomers since the 1970s. Our solar system adheres neatly to the laws of physics; the outer planets orbit the Sun at lower speeds than the inner ones. Further away from the Sun there is less gravity, so for example Neptune would fly off into deep space if it would move as fast as Venus. In galaxies however, we observe that the outer stars move at about the same speed as stars closer to the galaxy centre. Astronomers can only explain this by assuming an invisible source of gravity between the stars. They call this source dark matter.

Later, it appeared that there are also extra sources of gravity between galaxies. Clusters of galaxies contain hot gas that they could never hold on to accounting only for the mass of their visible stars. And the large-scale structure of the Universe has a web-like structure with luminous filaments of interconnected galaxies. Computer simulations cannot replicate this structure without adding dark matter to the equation. Dark matter should form a ‘skeleton’ with channels into which ordinary matter falls.

Euclid investigates the presence of dark matter by looking at subtle distortions in the images of galaxies. If there is (dark) matter anywhere along the line of sight, it will deflect the light from a galaxy and thus distort its image. If many galaxies show a distortion towards a specific direction, this indicates a clump of dark matter. With a database of billions of galaxies, Euclid can unravel the skeleton of dark matter. The sharpness or blurriness of the skeleton may reveal something about the origin of dark matter. Deviations in the skeleton from what the standard model predicts would indicate inaccuracies in that model.

Euclid has two instruments on board. The Visible Instrument (VIS) takes photographs in visible light and measures the distortions of galaxies with an accuracy of 0.18 arcseconds. It also gives a clear view of whether a galaxy is the result of a merger or just a standalone galaxy. The Near-Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP) produces spectra in the infrared, which astronomers use to determine the extent to which a galaxy’s spectrum has shifted to longer wavelengths. This gives the amount of ‘redshift’ and thus the speed at which a galaxy is moving away from us.

Both instruments have a wide field-of-view of 0.57 square degrees, almost three times the size of the full moon. This enables Euclid to photograph a third of the sky during its 6-year mission, resulting in a database of billions of galaxies.