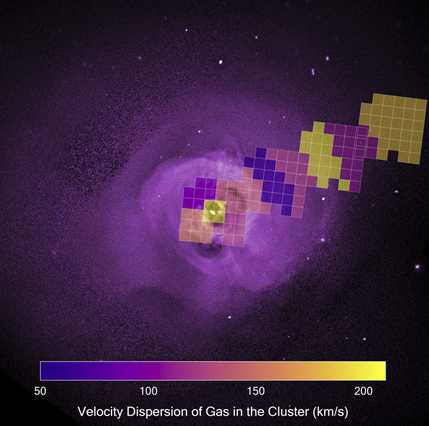

The XRISM telescope has mapped the gas turbulence inside the Perseus galaxy cluster for the first time. Gas flows turn out to have higher speeds at the centre and the outskirts, with less turbulence in between. These findings indicate that the supermassive black hole at the centre may play a crucial role in keeping the cluster at millions of degrees, preventing the gas from cooling enough to form new stars. The XRISM team, including SRON astronomers, publish their results in

The history of the universe is an interplay between two opposing forces. Gravity draws galaxies together, while dark energy pushes them apart. While the universe at large is expanding due to dark energy, there are some places where gravity wins by drawing hundreds of galaxies and their dark matter together in close proximity, forming galaxy clusters. The combined gravity of these galaxies collects gas from the surroundings and heats it to tens of millions of degrees, more than five thousand times as hot as the surface of the sun. The gas becomes a plasma so hot that it emits X-rays.

Perseus Cluster

The brightest galaxy cluster in the X-ray sky is the Perseus cluster. Astronomers expect that this intergalactic plasma is not simply standing still but experiencing its own kind of weather. The atmosphere of Perseus should be a tempest, with gas travelling hundreds of kilometers per second; however, clusters are so large, millions of light-years across, that it is impossible to see these gas motions in real time.

Blue- and redshift

Enter XRISM, developed by JAXA and NASA in collaboration with SRON. XRISM is providing astronomers with an unprecedented view of the universe by breaking down X-rays into a wide palette of different colors. Different chemical elements each have their own color fingerprint, and this shifts to the blue or to the red if that atom is going towards or away from us. This allows us to see how fast the plasma is moving, painting a dynamic picture of many clusters for the first time.

striking pattern

XRISM mapped the velocities of the intergalactic plasma in Perseus across an area extending 800 thousand light years and revealed a striking pattern. The velocity spread of the plasma is ~200 km/s in the centre of the cluster, slowing down to ~80 km/s as you look outward, then gaining speed towards larger radii, reaching ~200 km/s again. Plotting these velocities from the cluster centre outwards, this forms a V-shaped profile. However, to understand the origin of these motions, we must first determine the size of the gas flows, what astronomers refer to as scale.

Hurricanes and tornadoes

Gas motions act very differently depending on their scale. Think of the difference between hurricanes and tornadoes. Hurricanes act over a much larger area than tornadoes, but tornadoes can do a lot of damage very quickly to a small area. Typically, large scale gas motions create chaotic, small-scale motions, what physicists call turbulence. The turbulence you feel on an airplane is often caused by jet streams, massive air currents that circle the globe. These large-scale flows spawn small-scale vortices, which themselves create even smaller, chaotic air currents that you experience from your airplane seat.

smaller-scale motions in the centre

Something similar happens in the gas between galaxies. Because the centre of a cluster is much brighter than the outskirts, XRISM measures smaller-scale motions in the centre than it does on the outskirts. That means that even though the velocity spread in the center and outskirts are similar, they act on widely different scales. XRISM observes strong, small-scale motions in the cluster centre, which are embedded in large-scale flows that permeate the entire cluster.

supermassive black hole

We know that the large-scale flows come from the formation and growth of the Perseus cluster across cosmic time, but what is the origin of these small-scale motions? The obvious candidate is the supermassive black hole (SMBH) that resides at the centre of the cluster, 200 times more massive than our own Galaxy’s SMBH. Black holes are often portrayed as cosmic vacuum cleaners, relentlessly sucking in everything nearby. In reality, they are remarkably messy eaters: most of the gas drawn toward them is flung back in the form of powerful jets and winds. These outflows continuously inject energy and momentum into the surrounding intergalactic atmosphere, stirring the hot gas and driving small-scale motions. XRISM disentangles this dynamic process in a cluster for the very first time.

Heat prevents star formation

SMBH feedback, like the kind that has been seen in Perseus, could be a key barrier to the lack of star formation we see in galaxies in the modern universe. Most of the stars in the universe were formed nearly 10 billion years ago, a time known as “cosmic noon”. After this time, new stars become rarer and rarer. The reasons for this lack of new star formation are still not fully understood, but SMBH feedback may play a role. In clusters like Perseus, their atmospheres are expected to cool down over time and feed star formation. However, something is heating the atmosphere and preventing this process. SMBH feedback is the prime candidate for this heating, but astronomers don’t yet understand how the SMBH communicates with the gas. XRISM’s measurements of gas motions in Perseus indicate that turbulence driven by the SMBH may be playing an important role in heating the cluster atmosphere.