The far-infrared detector that SRON is developing for NASA’s PRIMA space telescope will receive support from the NSO Instrument Programme. This will enable SRON to carry out flight tests before NASA makes a final decision on PRIMA.

How did the very first and therefore oldest galaxies in our Universe come into being? Under what circumstances are planets born? And what is the origin of all the matter around us? These are three pressing questions that astronomers are seeking answers to. However, a measuring instrument that can help them find those answers has not yet been invented. SRON is set to change that.

Anyone who has ever sat around a campfire knows that there are different types of electromagnetic radiation, explains Jochem Baselmans of SRON and TU Delft. When you look at that crackling fire, your eyes see wavelengths of roughly 380 to 760 nanometres. Once the fire has gone out, you can’t see anything, but you can still feel the heat from the smouldering wood. That’s infrared radiation, with wavelengths longer than 760 nanometres.

Astronomers have now learned to “capture” some of this infrared radiation, which also comes to Earth from space, using instruments. For example, the James Webb Space Telescope, equipped with the partly Dutch instrument MIRI, takes beautiful images of stars and planets in the mid-infrared. But it cannot see all infrared radiation.

A notoriously difficult-to-capture portion consists of wavelengths from 30 to 300 micrometres. And it is precisely in these wavelengths that some of the biggest secrets of our Universe are hidden.

Chicken and egg in space

The biggest challenge for engineer Baselmans and his colleagues is a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma: ‘A space telescope costs around a billion euros. You only build one if you are certain that the heart of that telescope, in this case a far-infrared detector, works properly. But who is going to pay for the development of a far-infrared detector if there is no space mission yet on which it can fly?

“Brilliant”, is therefore Baselmans’ classification for NSO’s Instrument Programme. With financial support from this government programme, SRON can bring the development of the far-infrared detector a few steps closer. So close, in fact, that NASA will order one for its latest infrared space telescope, PRIMA, in 2026.

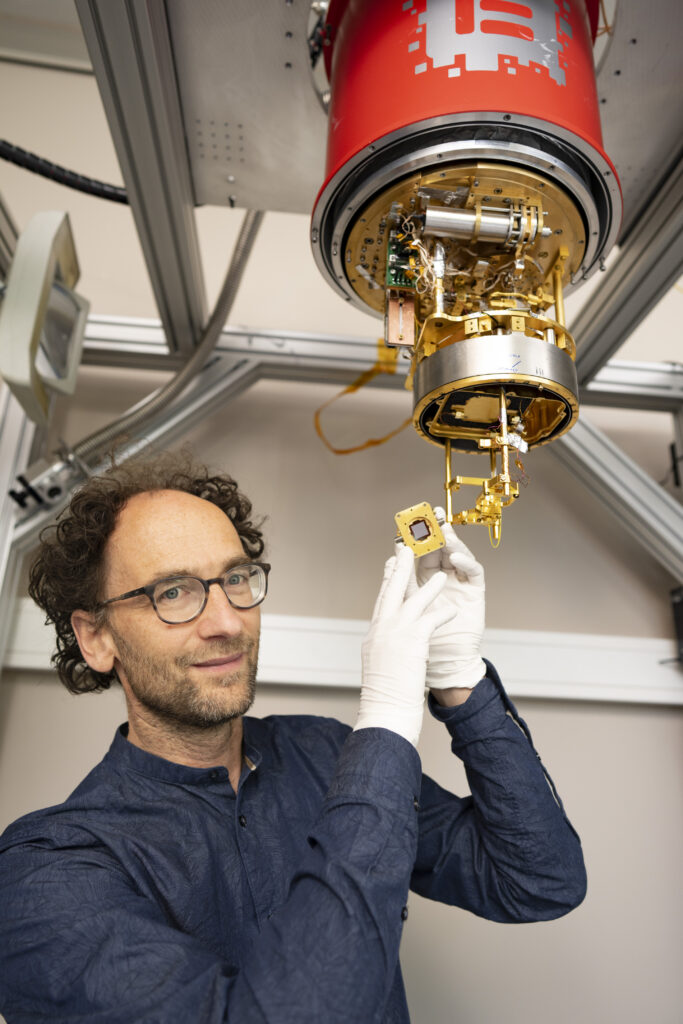

In order to get the Dutch far-infrared receiver on NASA’s PRIMA mission, SRON must demonstrate that the detector based on superconducting nanotechnology can be built and that all pixels work. In addition, the detector must survive launch and the extreme conditions of space. A prototype will therefore first undergo vibration tests that simulate a rocket launch. It will then be cooled to extremely low temperatures in a cryostat and bombarded with simulated space radiation. ‘Thanks to the contribution from the Instrument Programme, we can carry out all these tests before NASA makes its final decision on the PRIMA mission in 2026,’ says Baselmans.

A million times more sensitive

Baselmans believes there is a good chance that this far-infrared mission will go ahead. This is because a far-infrared detector opens up a whole new field of research in astronomy. ‘The James Webb Space Telescope was a hundred times more sensitive than anything we had before. With PRIMA, that factor is a million. This means it can observe objects down to a few tens of Kelvin,’ explains Baselmans. ‘Suddenly, you can see the oldest galaxies and planet formation, right through the gas and dust that obscures that light from other telescopes.’

SRON started developing a far-infrared detector more than twenty years ago. Since then, the institute has built up an intensive collaboration with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and with various scientists worldwide who can’t wait for the instrument to be ready: ‘Astronomers tell us that they can’t see anything in the far-infrared yet. So we say: we’re going to build something for that. It may take us twenty years, but we, as a relatively small country, can do it – as the first in the world.’

The is an edited version of an NSO press release.