(English below Dutch)

SRON-wetenschappers ontwikkelen een detectietechnologie (TES) die de energie van individuele fotonen registreert, bijvoorbeeld voor röntgenstraling uit het verre heelal. Tot nu werd aangenomen dat de bedrading op de detectiechip een intrinsieke grilligheid in de nauwkeurigheid met zich meebrengt. Het onderzoeksteam heeft nu ontdekt dat er toch ruimte is voor verbetering. Publicatie in Physical Review Applied.

Röntgenstraling biedt ons zicht op de verschijnselen in het heelal waar met reusachtige hoeveelheden energie wordt gesmeten. Heet gas tussen de honderden sterrenstelsels in clusters, actieve zwarte gaten, supernovae en dubbele neutronensterren zijn daar enkele voorbeelden van. Maar om van het uitzicht te genieten moet je doorgaans een flink stuk klimmen. In het geval van hoogenergetische verschijnselen moet je zelfs tot de ruimte reiken. De aardatmosfeer blokkeert namelijk het meeste röntgenlicht. Daarom doen röntgentelescopen hun waarnemingen vanuit de ruimte. Wetenschappers van SRON ontwikkelen voor dat soort ruimtetelescopen een detectietechnologie die de energie van individuele fotonen registreert, om zelfs van de verste röntgenverschijnselen het spectrum te bepalen—Transition Edge Sensors (TES).

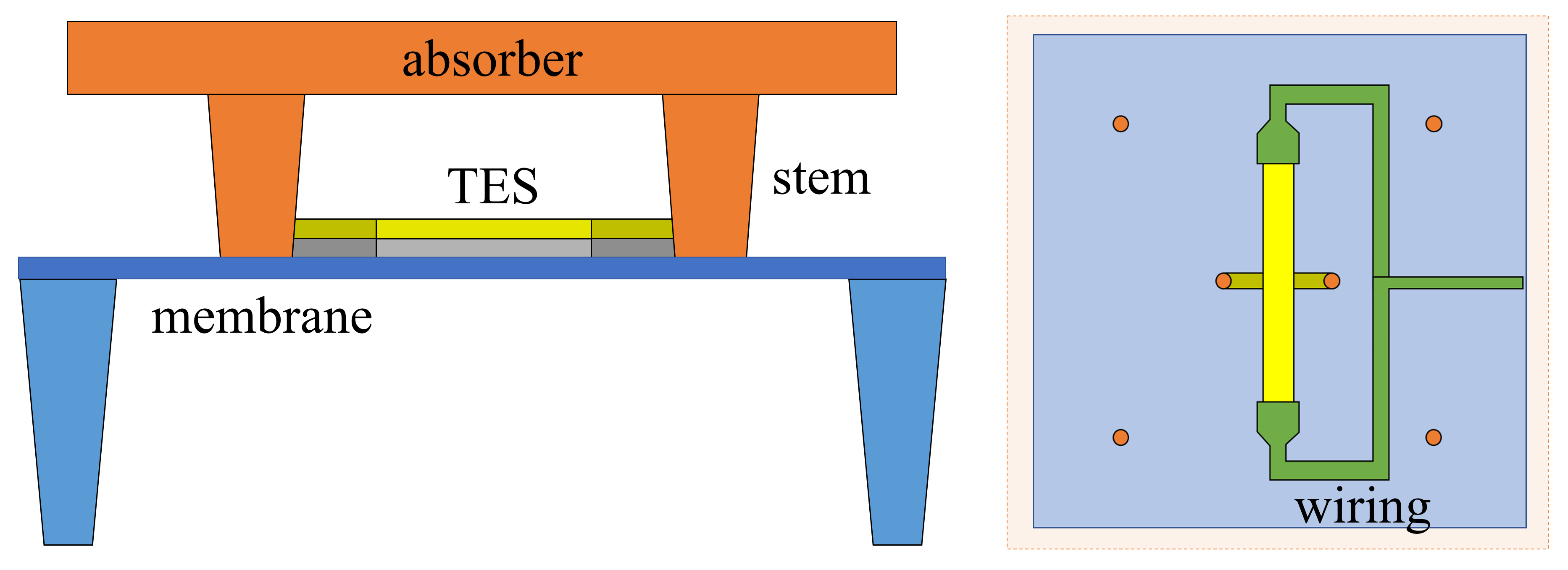

Om de energie van een foton over te brengen op de detectoren, gebruiken TES-detectoren een zogenoemde absorber, een paddenstoel-achtig metalen dakje boven de detector, die ermee verbonden is via twee poten. Het SRON-onderzoeksteam onder leiding van Jian-Rong Gao heeft nu een manier gevonden om het ontwerp van de koppeling tussen deze absorbers en de TES verder te verbeteren.

TES-detectoren werken bij temperaturen nabij het absolute nulpunt, zodat ze supergeleidend zijn. Door ze te balanceren op het randje tussen supergeleiding en de normale toestand, kunnen ze worden gebruikt als gevoelige thermometers. De energie van een enkel foton is voldoende om het materiaal genoeg op te warmen om de balans richting normale toestand te tippen. Dit is uit te lezen als een verandering in de stroom die door de detectoren loopt, proportioneel met de energie van het inkomende foton.

Om nauwkeurig deze energie te bepalen, moeten de detectoren zo netjes mogelijk werken. Maar in de praktijk zien we vaak grillig gedrag, zoals oscillerende stroomsterktes afhankelijk van waar op de supergeleidende transitie de detector werkt. Er werd algemeen aangenomen dat de overgang tussen de TES en de bedrading op de detectorchip verantwoordelijk was voor dit gedrag. ‘Maar tot onze verbazing zien we dat het dunner maken van de poten van de absorber de oscillaties aanzienlijk vermindert,’ zegt eerste auteur Martin de Wit.

De ontdekking betekent dat er wel degelijk nog winst te behalen is in het ontwerp van de TES. De Wit: ‘Aan die overgang is niets te doen, die moet er gewoon zijn als je met deze detectoren wilt werken. Gelukkig zien we nu dus dat een groot deel van het ongewenste gedrag niet komt door deze overgang, maar te maken heeft met hoe wij de absorber verbinden met de TES. En daar hebben we wél invloed op.’

Publicatie

M. de Wit, L. Gottardi, E. Taralli, K. Nagayoshi, M.L. Ridder, H. Akamatsu, M.P. Bruijn, R.W.M. Hoogeveen, J. van der Kuur, K. Ravensberg, D. Vaccaro, J-R. Gao,† and J-W.A. den Herder, ‘Impact of the absorber coupling design for Transition Edge Sensor X-ray Calorimeters’, Physical Review Applied

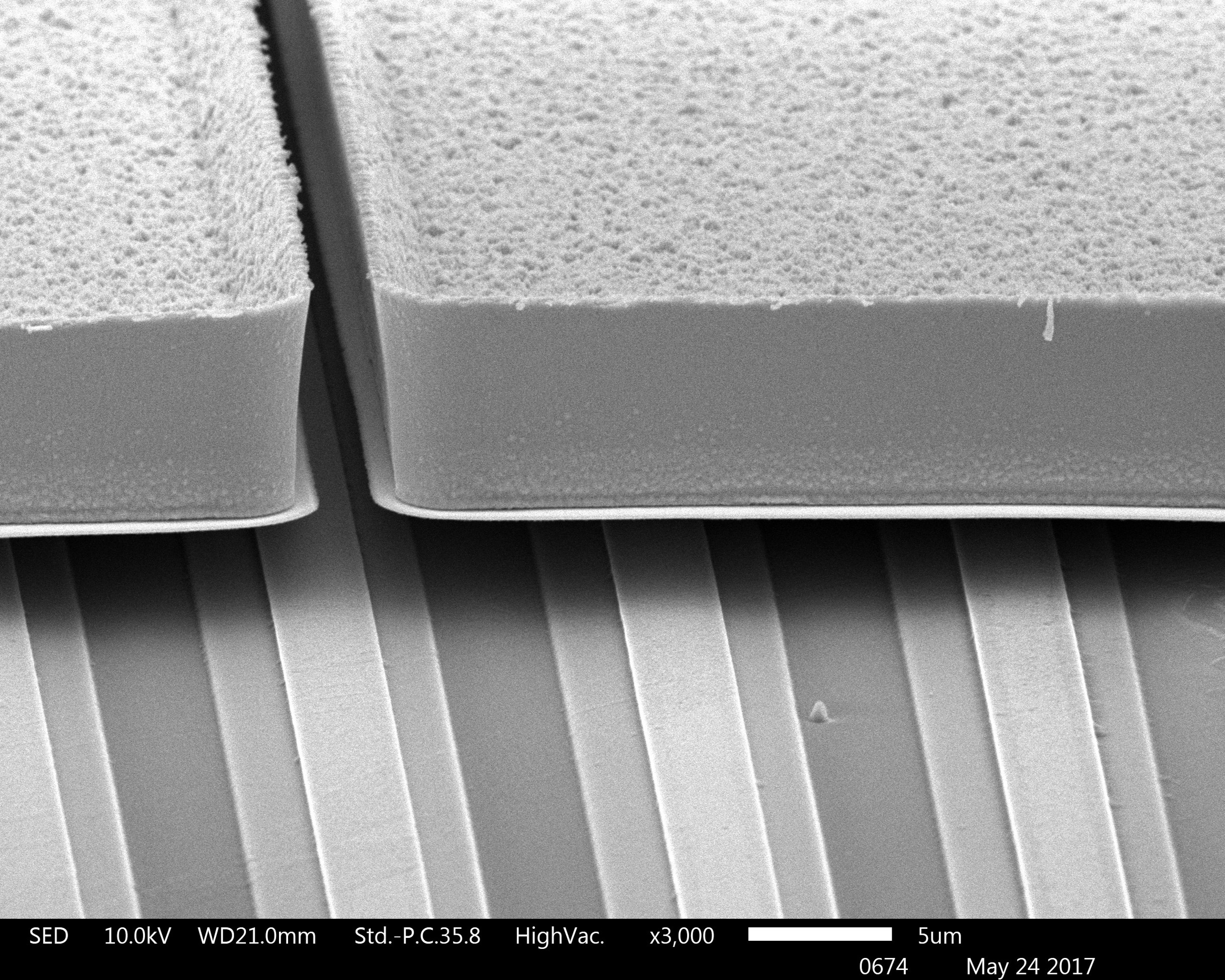

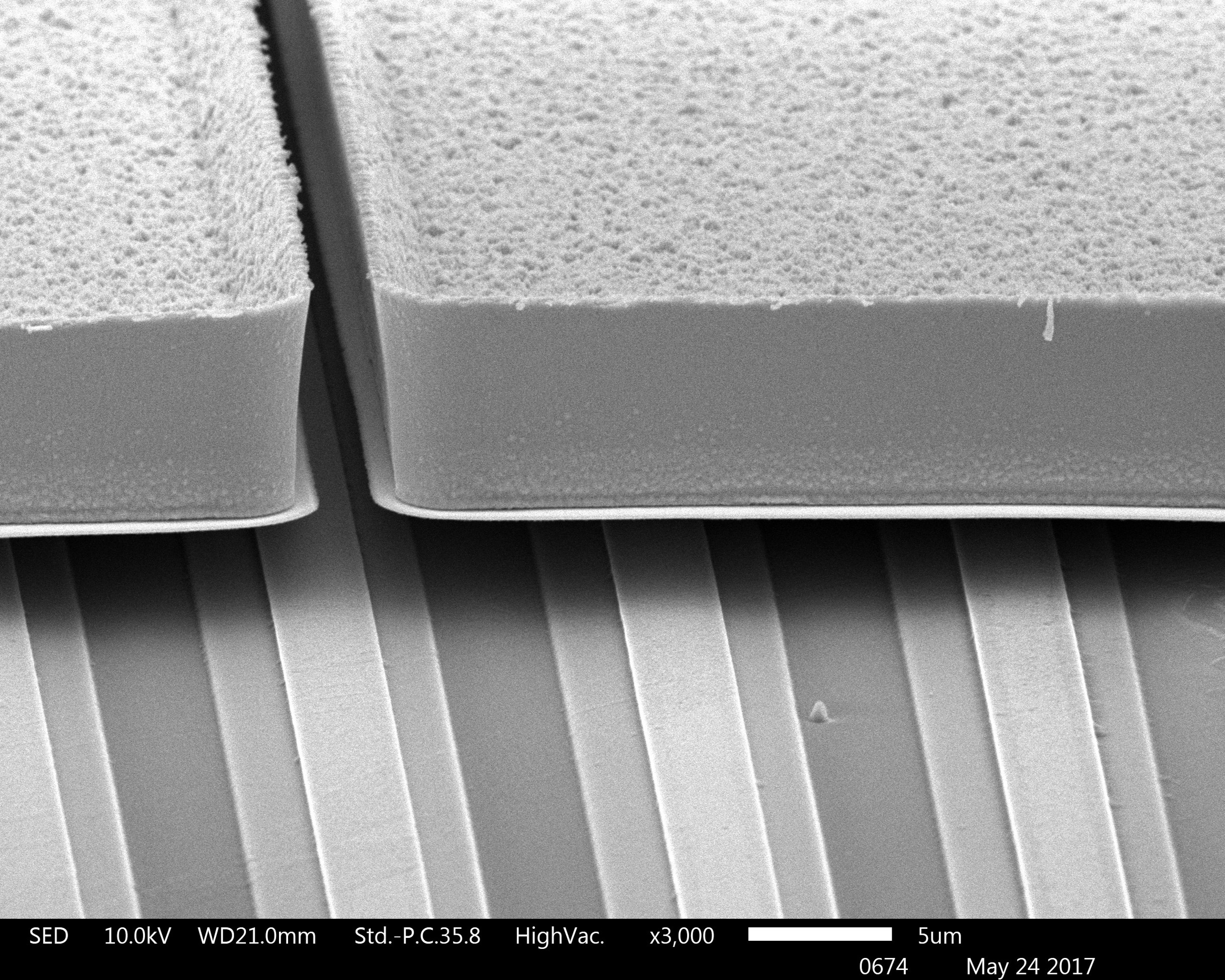

Headerfoto: Foto gemaakt met elektrononenmicroscoop van twee absorbers boven supergeleidende bedrading.

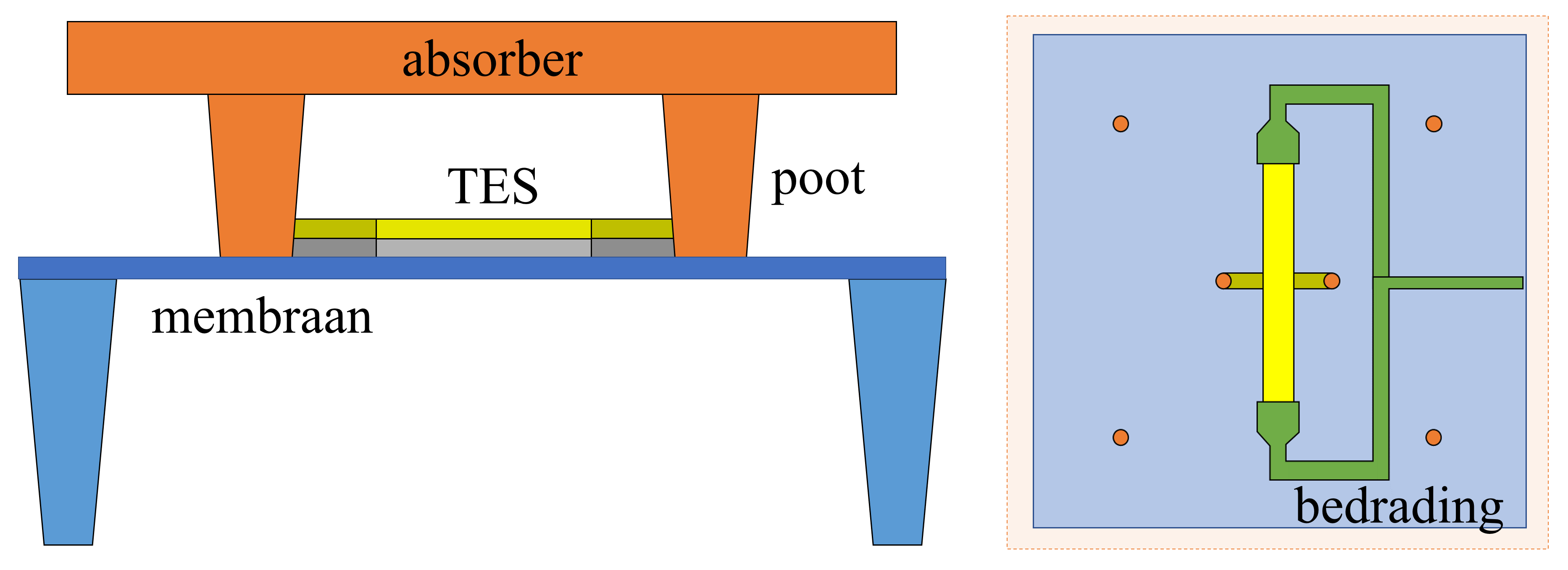

Foto onder: Links: Schematische weergave van ontwerp van de koppeling tussen de absorbers en de TES. De absorber is een paddenstoel-achtig metalen dakje dat de energie van inkomende fotonen over moet brengen op de TES. Als de poten van de absorber dunner gemaakt worden, verminderen de oscillaties in de stroomsterktes. Rechts: Eerder werd aangenomen dat de overgang tussen de TES (geel) en de bedrading (groen) een fundamentele limiet stelde op de nauwkeurigheid.

Accuracy limit TES detector less fundamental than assumed

Scientists at SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research are developing a detection technique (TES) that measures the energy of individual photons, for example in X-rays from the distant universe. Until now, it was assumed that the wiring on the detector chip brings along an inherent whimsicality in accuracy. The research team has now discovered that there is room for improvement after all. Publication in Physical Review Applied.

X-rays offer us a view of the high-energetic phenomena in the Universe. Hot gas inside clusters of hundreds of galaxies, active black holes, supernovae and binary neutron stars are just a few examples. But to enjoy the view, you usually have to climb to high altitudes. In the case of high-energy phenomena, you have to go all the way to space. The Earth’s atmosphere blocks most X-ray light. That is why X-ray telescopes do their job from space. Scientists at SRON are developing a detection technology—Transition Edge Sensors (TES)—for these space telescopes that measures the energy of individual photons to obtain a spectrum of even the most distant X-ray phenomena.

To transfer the energy of a photon to the detectors, TES technology makes use of an absorber—a metal mushroom-shaped roof above the detector—connected via two stems. The SRON research team led by Jian-Rong Gao has now found a way to further improve the design of the coupling between these absorbers and the TES.

TES detectors operate at temperatures near absolute zero, making them superconducting. By keeping them balanced on the edge of superconductivity and the normal conduction state, they can be used as sensitive thermometers. The energy of a single photon is sufficient to heat up the material enough to tip the balance toward the normal state. This is read out as a change in the current flowing through the detectors, proportional to the energy of the incoming photon.

To accurately determine this energy, the detectors should work as neatly as possible. But in practice we often see whimsical behavior, such as oscillating currents depending on where at the superconductive transition the detector operates. Until now it was assumed that the connection points between the TES and the wiring on the detector chip was responsible for this behavior. ‘But to our surprise, we see that making the absorber stems thinner significantly reduces the oscillations,’ says first author Martin de Wit.

The discovery means that there is, after all, still room for improvement in the design of the TES. De Wit: ‘There is nothing you can do about those connection points, they simply have to be there if you want to work with these detectors. Fortunately, we now discovered that a large part of the unwanted behavior is not due to these connection points, but has to do with how we connect the absorber to the TES. And we do have a way of influencing that.’

Publication

M. de Wit, L. Gottardi, E. Taralli, K. Nagayoshi, M.L. Ridder, H. Akamatsu, M.P. Bruijn, R.W.M. Hoogeveen, J. van der Kuur, K. Ravensberg, D. Vaccaro, J-R. Gao,† and J-W.A. den Herder, ‘Impact of the absorber coupling design for Transition Edge Sensor X-ray Calorimeters’, Physical Review Applied

Header image: Electron microscope picture of two absorbers on top of superconducting wiring

Picture below: Left: Schematic representation of the design of the coupling between the absorbers and the TES. The absorber is a metal mushroom-shaped roof that has to transfer the energy of the incoming photons to the TES. If the stems of the absorber are made thinner, we see a decrease in the oscillations in the current. Right: Until now it was assumed that the connection points between the TES (yellow) and the wiring (green) pose a fundamental limit on the accuracy.