(English follows Dutch)

De zoektocht naar buitenaards leven is tot nu toe vooral gericht op planeten die op een afstand van hun ster staan waar vloeibaar water aan het oppervlak mogelijk is. Maar in ons zonnestelsel lijkt het meeste vloeibare water zich buiten dit gebied te bevinden. Manen van koude gasreuzen worden door getijdekrachten opgewarmd tot boven het vriespunt. Het zoekgebied in andere planetenstelsels wordt dus groter als we ook de manen beschouwen. Onderzoekers van SRON en de RuG hebben nu een formule gevonden om de aanwezigheid en de diepte van ondergrondse oceanen in zulke ‘exomanen’ te berekenen.

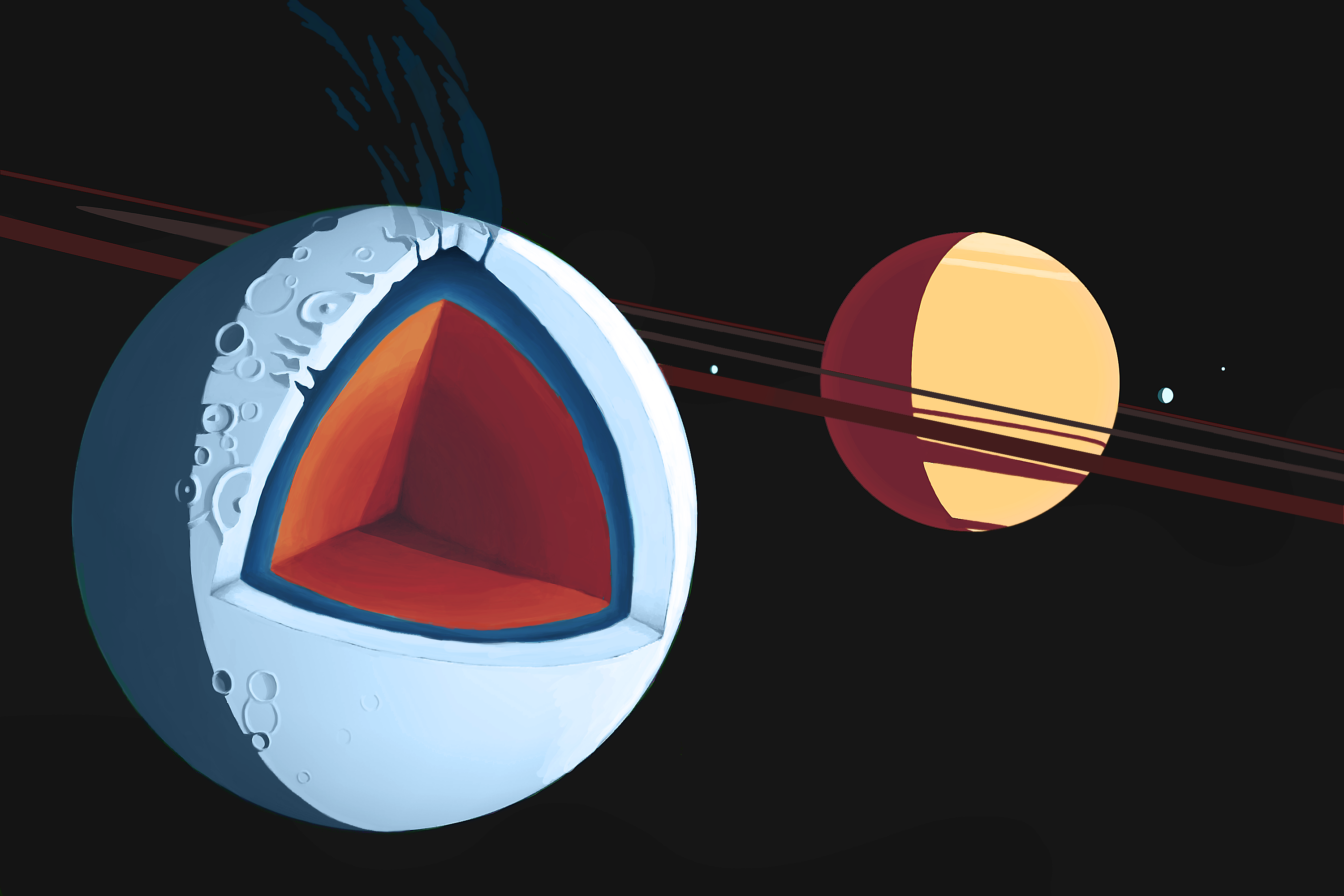

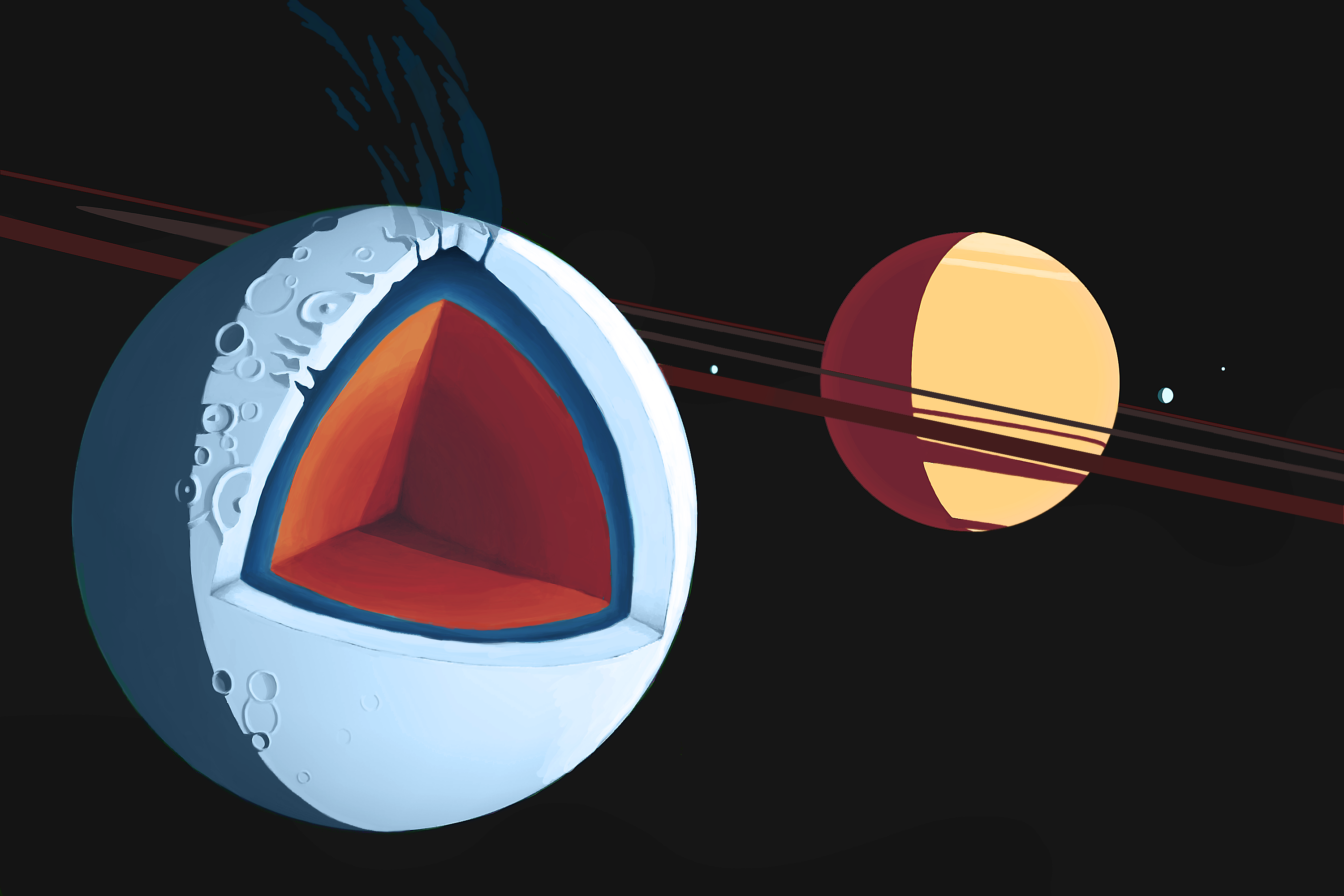

In de zoektocht naar buitenaards leven kijken we tot nu toe vooral naar planeten die op onze Aarde lijken en op een afstand van hun moederster staan waar de temperatuur ligt tussen het vries- en kookpunt van water. Maar als we uitgaan van ons eigen Zonnestelsel liggen er meer mogelijkheden in de manen dan de planeten. Enceladus, Europa en een stuk of zes andere manen van Jupiter, Saturnus, Uranus en Neptunus herbergen mogelijk een ondergrondse oceaan. Die liggen allemaal ver buiten de reguliere leefbare zone—het is er letterlijk ijskoud aan het oppervlak—maar getijdewisselwerking met hun moederplaneet warmt hun binnenste op.

Exoplaneetjagers zoals de toekomstige PLATO-telescoop—waar ook SRON aan werkt—hebben met manen een groter jachtgebied wat betreft de speurtocht naar leven. Als er een zogenoemde exomaan wordt gevonden, is het zaak om erachter te komen of er vloeibaar water mogelijk is. Onderzoekers van SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research en de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (RuG) hebben nu een formule afgeleid waarmee je voor elke maan kunt berekenen of er een ondergrondse oceaan aanwezig is en hoe diep die zich bevindt.

‘Volgens de meest gangbare definitie heeft ons Zonnestelsel twee planeten met een leefbaar oppervlak: de Aarde en Mars,’ zegt eerste auteur Jesper Tjoa. ‘Volgens een soortgelijke definitie zijn er ongeveer acht manen met mogelijk leefbare omstandigheden onder hun oppervlak. Als je dat doortrekt naar andere planetenstelsels zouden er viermaal zoveel leefbare exomanen kunnen zijn als leefbare exoplaneten.’ Vanuit die motivatie leidde hij met zijn begeleiders Floris van der Tak (SRON/RuG) en Migo Mueller (SRON/RuG/Sterrewacht Leiden) een formule af die een ondergrens geeft voor de oceaandiepte. Factoren die meespelen zijn bijvoorbeeld de diameter van de maan, de afstand tot de planeet, de dikte van het maangruis aan het oppervlak en de thermische geleidbaarheid van de ijs- of grondlaag daaronder. De eerste twee zijn meetbaar, de andere twee moeten we schatten op basis van ons zonnestelsel.

Hoewel ondergronds leven lastiger te vinden is dan leven aan het oppervlak, is het in de nabije toekomst wel degelijk mogelijk om een hint te verkrijgen. Tjoa: ‘Waarnemers bestuderen het sterlicht dat door de atmosfeer van exoplaneten schijnt. Dan kunnen ze bijvoorbeeld zuurstof herkennen. Als ze toekomstige telescopen op exomanen richten zien ze mogelijk geisers zoals op Enceladus, die afkomstig zouden kunnen zijn uit een ondergrondse oceaan. In principe zijn daarin dan ook tekenen van leven te herkennen.’

Dl = Rs – [4πĖ-1endo(K(Tl) – K(Trego)) + (Rs – Drego)-1]-1

Waarbij Dl is de smeltdiepte, Rs is de straal van de maan, Ėendo is de totale gegenereerde interne warmte, Drego is de dikte van het maangruis, Tl is de smelttemperatuur van waterijs gegeven de hoeveelheid vervuiling, Trego is de temperatuur van de ijs- of grondlaag onder het maangruis en K(T) is de geïntegreerde thermische geleidbaarheid van de ijs- of grondlaag.

Publicatie

J.N.K.Y. Tjoa, M. Mueller, and F.F.S. van der Tak, ‘The subsurface habitability of small, icy exomoons’, Astronomy & Astrophysics

Astronomers find formula for subsurface oceans in exomoons

So far, the search for extraterrestrial life has focused on planets at a distance from their star where liquid water is possible on the surface. But within our Solar System, most of the liquid water seems to be outside this zone. Moons around cold gas giants are heated beyond the melting point by tidal forces. The search area in other planetary systems therefore increases if we also consider moons. Researchers from SRON and RuG have now found a formula to calculate the presence and depth of subsurface oceans in these ‘exomoons’.

In the search for extraterrestrial life, we have so far mainly looked at Earth-like planets at a distance from their parent star where the temperature is between the freezing and boiling point of water. But if we use our own Solar System as an example, moons look more promising than planets. Enceladus, Europa and about six other moons of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune may harbor a subsurface ocean. They all reside far outside the traditional habitable zone—it is literally freezing cold on the surface—but tidal interaction with their host planet heats up their interior.

With moons entering the equation, exoplanet hunters such as the future PLATO telescope—which also SRON is working on—gain hunting ground regarding the search for life. When astronomers find a so-called exomoon, the main question is whether liquid water is possible. Researchers from SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research and the University of Groningen (RuG) have now derived a formula telling us whether there is a subsurface ocean present and how deep it is.

‘According to the most common definition, our Solar System has two planets with a habitable surface: Earth and Mars,’ says lead author Jesper Tjoa. ‘By a similar definition there are about eight moons with potentially habitable conditions below their surface. If you extend that to other planetary systems, there could be four times as many habitable exomoons as exoplanets.’ With this in mind, Tjoa and his supervisors Floris van der Tak (SRON/RuG) and Migo Mueller (SRON/RuG/Leiden Observatory) derived a formula that provides a lower limit for the ocean depth. Among the factors involved are the diameter of the moon, the distance to the planet, the thickness of the gravel layer on the surface and the thermal conductivity of the ice or soil layer below. The first two are measurable, the other two have to be estimated based on our Solar System.

Although underground life is more difficult to find than life on the surface, it will be possible to obtain a hint in the near future. Tjoa: ‘Observational astronomers study starlight shining through the atmospheres of exoplanets. They can for example identify oxygen. When they point future telescopes at exomoons, they may see geysers like on Enceladus, stemming from a subsurface ocean. In principle you could recognize signs of life that way.’

Dl = Rs – [4πĖ-1endo(K(Tl) – K(Trego)) + (Rs – Drego)-1]-1

Wherein Dl is the melting depth, Rs the moon’s radius, Ėendo the total generated endogenic heat, Drego the regolith thickness, Tl the liquidus temperature, Trego the temperature underneath the regolith and K(T) the integrated conductivity.

Publication

J.N.K.Y. Tjoa, M. Mueller, and F.F.S. van der Tak, ‘The subsurface habitability of small, icy exomoons’, Astronomy & Astrophysics