De zwaartekracht op neutronensterren is zo hoog dat invallende materie zelfs aan het oppervlak kan fuseren in een kernexplosie. Astronomen signaleren soms in de nagloed van zulke explosies mysterieuze fluctuaties. SRON-wetenschapper Jean in ’t Zand formuleerde hier samen met collega’s een theorie over, die ze nu bevestigd zien met aanvullende data van het Neil Gehrels Swift Observatorium. Publicatie in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

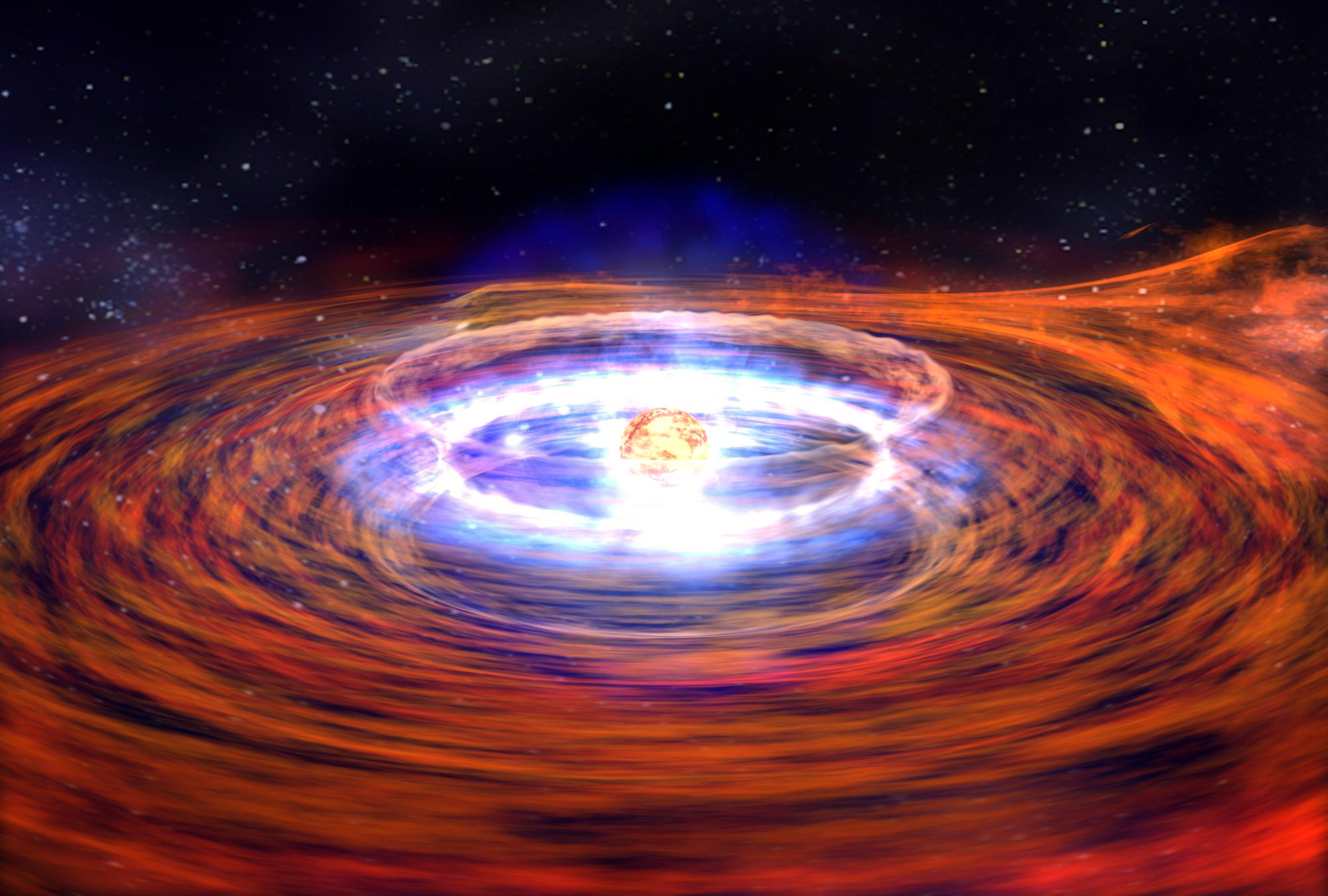

Neutronensterren behoren tot de meest extreme objecten in ons heelal. Ze zijn ongeveer twintig kilometer groot en draaien tot honderden malen per seconde om hun as. De zwaartekracht aan hun oppervlak is enkele miljarden malen groter dan op aarde. Een suikerklontje weegt op een neutronenster bij benadering net zoveel als de Eiffeltoren in Parijs. Die hoge zwaartekracht zorgt voor een enorme gasdruk, zelfs dicht onder het oppervlak. Al op een meter diepte kan er spontaan kernfusie optreden. De eigen materie van neutronensterren—losse neutronen—fuseert niet, maar als er waterstof en helium vanuit een omringende accretieschijf op het oppervlak terechtkomt, kan er een explosie optreden door een kettingreactie van kernfusie—een waterstofbom in extremis. Zulke bommen zijn zo helder dat we ze door de hele Melkweg kunnen detecteren.

Astronomen signaleren na sommige explosies mysterieuze fluctuaties in de nagloed. SRON-wetenschapper Jean in ’t Zand en zijn mede-onderzoekers, waaronder de Utrechtse bachelorstudent Maarten Kries, onderzoeken dit raadsel en hebben hun dataset nu uitgebreid met gegevens die de Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) en de X-ray Telescope (XRT) op het Amerikaanse Neil Gehrels Swift Observatorium de afgelopen veertien jaar hebben verzameld in de ruimte. Die bevestigen hun eerdere theorie.

Theorie

In ’t Zand en zijn groep formuleerden tijdens eerder onderzoek een theorie dat de explosies de accretieschijf rond de neutronenster opschudden, zodat er wolken ontstaan boven en onder de verder platte schijf. Die wolken absorberen en reflecteren vervolgens de felle straling die de explosies uitzenden. Onze telescopen vangen daarom soms meer en soms minder straling op, wat de fluctuaties in helderheid verklaart. De aanvullende data van de twee telescopen op het Swift Observatorium bevestigen deze theorie.

Swift Observatorium

Het Swift Observatorium is oorspronkelijk bedoeld om gammaflitsen waar te nemen, terwijl de kernexplosies op neutronensterren zich dankzij hun temperatuur van ongeveer tien miljoen graden uiten als röntgenflitsen. Het spectrale bereik van de BAT en XRT is echter breed genoeg om ook röntgenstraling op te pikken.

Publicatie

J. J. M. in ’t Zand, M. J. W. Kries, D. M. Palmer, and N. Degenaar, ‘Searching for the most powerful thermonuclear X-ray bursts with the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory’, Astronomy & Astrophysics 621, A53 (2019)

Deze publicatie is door A&A verkozen tot Highlight.

———————————————————————————————————————————–———————————————————————————————————————————–

New data confirms theory on mysterious afterglow neutron stars

Neutron stars have such a high gravity that even on their surface inflowing matter can fuse in a nuclear explosion. In the afterglow of these explosions, astronomers sometimes spot mysterious fluctuations. SRON scientist Jean in ‘t Zand, together with his colleagues, proposed a theory, which they now see confirmed by additional data from the Neil Gehrers Swift Observatory. Publication as a highlight in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Neutron stars belong to the most extreme objects in our Universe. They are about twenty kilometer in diameter and spin up to hundreds of times around their axis within a second. Their surface gravity is a few billion times larger than Earth’s. A sugar cube on a neutron star weighs about the same as the Eiffel tower in Paris. This enormous gravity generates a huge gas pressure, even close to the surface. Nuclear fusion can already spontaneously ignite at a depth of just one meter. Neutron stars are composed of individual neutrons, which don’t fuse, but when hydrogen and helium hit the surface from a surrounding accretion disk, an explosion can occur due to a chain reaction of nuclear fusion—a cosmic hydrogen bomb. Those bombs are bright enough that we can detect them from all across the Milky Way.

Astronomers detect mysterious fluctuations in the afterglow of some explosions. SRON scientist Jean in ‘t Zand and his fellow researchers, including Utrecht bachelor student Maarten Kries, study this phenomenon and have now extended their dataset with observations from the Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) and the X-ray Telescope (XRT) on the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, collected over the last fourteen years. Those confirm their previous theory.

Theory

In ‘t Zand and his team formulated a theory during previous research, proposing that the explosions disturb the accretion disk around the neutron star and consequently produce clouds above and underneath the otherwise flat disk. Those clouds then absorb and reflect the bright radiation emitted by the explosions. Therefore our telescopes collect varying amounts of radiation, which explains the fluctuations in brightness. The additional data from the two telescopes on the Swift Observatory confirms this theory.

Swift Observatory

The Swift Observatory is originally intended to detect gamma ray bursts. But the nuclear explosions on neutron stars express themselves in the form of X-rays bursts, due to their temperature of about ten million degrees. However, the spectral range of the BAT and XRT is broad enough to pick up X-rays as well.

Publication

J. J. M. in ’t Zand, M. J. W. Kries, D. M. Palmer, and N. Degenaar, ‘Searching for the most powerful thermonuclear X-ray bursts with the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory’, Astronomy & Astrophysics 621, A53 (2019)

This publication was selected as a Highlight by A&A.