Fuserende sterrenstelselclusters fungeren als natuurlijke laboratoria voor astronomen om kosmische verschijnselen te bestuderen. SRON-wetenschapper Igone Urdampilleta gebruikte de fuserende cluster Abell 3376 om te onderzoeken hoe elektronen met relativistische snelheden door het intracluster medium vliegen. Publicatie in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Terwijl je dit leest, vliegt het Andromedastelsel op onze Melkweg af met een snelheid van ruim honderd kilometer per seconde. Staat onze Zon een desastreuze botsing te wachten met een van de biljoen Andromedasterren, waarbij ze de Aarde in het geweld meesleurt? Gelukkig niet. Binnen een sterrenstelsel zijn de afstanden tussen sterren zo enorm dat als ze de grootte hadden van pingpongballetjes, ze nog steeds ongeveer duizend kilometer van elkaar zouden staan. Sterrenstelsels botsen niet; ze fuseren. Hetzelfde geldt voor clusters van sterrenstelsels. Ze bieden astronomen een kosmisch laboratorium om allerlei verschijnselen te bestuderen, zoals elektronen die versnellen binnen het gas tussen sterrenstelsels.

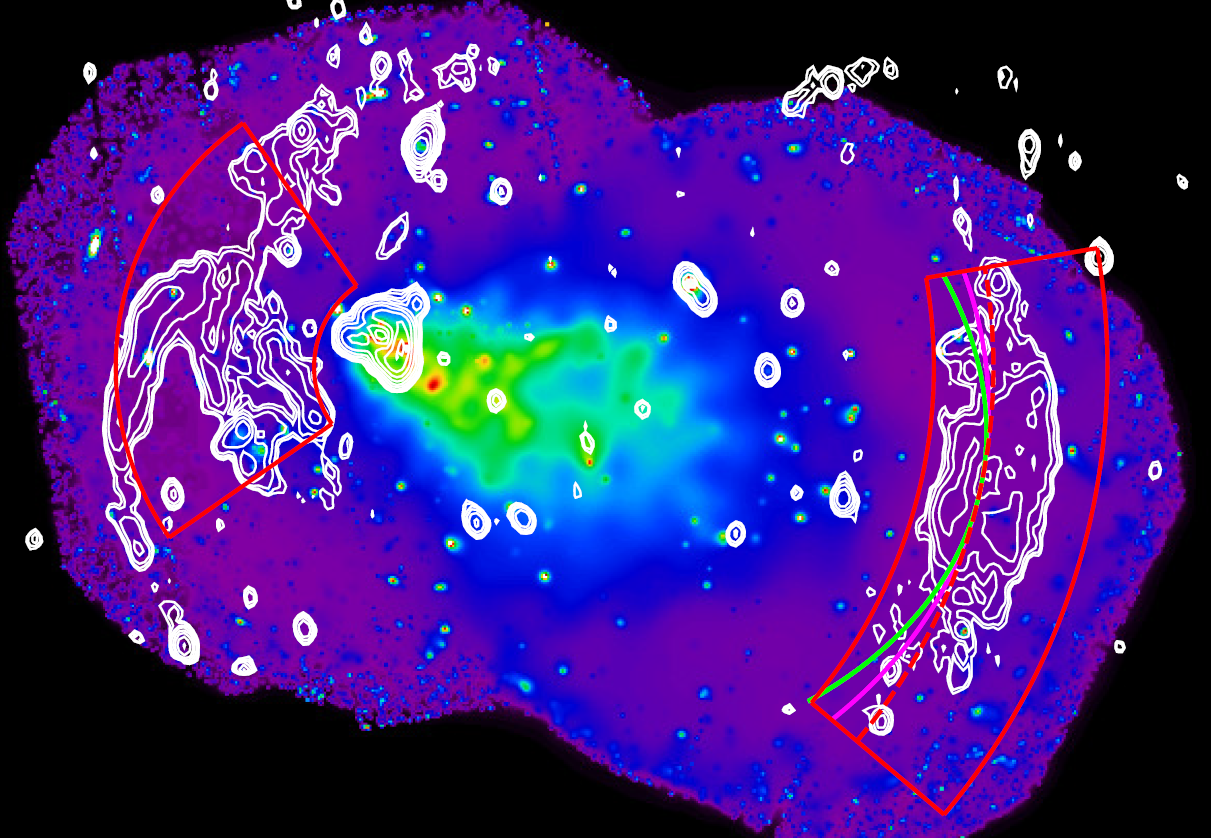

Tijdens de fusie warmt heet en diffuus gas tussen de sterrenstelsels verder op, wat turbulentie veroorzaakt. Sterrenkundigen noemen dit het intracluster medium (ICM), dat met slechts één deeltje per liter ontzettend ijl is. De ‘botsing’ veroorzaakt schokfronten die zich vanuit het centrum van het cluster een weg banen naar de buitengebieden. Doordat het ICM opwarmt, was Urdampilleta in staat om het te observeren via röntgenstraling, waarvoor ze voornamelijk het XIS-instrument gebruikte van de Japanse Suzaku ruimtetelescoop.

Urdampilleta en haar collega’s vergeleken hun röntgendata van schokfronten in de buitengebieden van Abell 3376 met radiometingen in diezelfde regio. In de periferie worden schokfronten meestal geassocieerd met radiostraling als gevolg van ofwel directe versnelling van elektronen—genaamd Diffusive Shock Acceleration—ofwel het opnieuw versnellen van reeds bestaande kosmische elektronen. De onderzoekers concluderen dat tenminste in het geval van de westelijke radiobron van Abell 3376, het mechanisme achter de elektronversnelling consistent lijkt te zijn met Diffusive Shock Acceleration.

Publicatie

I. Urdampilleta, H.Akamatsu, F. Mernier, J. S. Kaastra, J. de Plaa, T. Ohashi, Y. Ishisaki, and H. Kawahara, ‘X-ray study of the double radio relic Abell 3376 with Suzaku’, Astronomy & Astrophysics

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Merging galaxy cluster provides laboratory for accelerating electrons

Merging galaxy clusters provide natural laboratories for astronomers to study cosmic phenomena. SRON scientist Igone Urdampilleta uses the merger Abell 3376 to study how electrons rush through the intracluster medium at relativistic speeds. The findings point towards an acceleration mechanism called Diffusive Shock Acceleration. Publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

As we speak, the Milky Way is on collision course with the Andromeda Galaxy at a speed of over a hundred kilometers per second. Will our Sun violently collide with one of the trillion Andromeda stars, taking the Earth down with her? Fortunately, no. The distances between stars in a galaxy are so vast that if they were the size of ping pong balls, they would be about a thousand kilometers apart. Galaxies don’t collide, they merge. The same goes for clusters of galaxies. They provide astronomers with a cosmic laboratory for studying all kinds of phenomena, such as electrons accelerating through the gas in between galaxies. SRON scientist Igone Urdampilleta uses two merging clusters, who share the name Abell 3376, to study how electrons get accelerated up to relativistic energies.

During the merger, hot and diffuse gas between galaxies heats up and becomes turbulent. Astronomers call this the intracluster medium (ICM), which is extremely airy, containing just one particle per liter. The ‘collision’ causes shock fronts, propagating from the center to the outskirts of the cluster. Because the ICM becomes hot, Urdampilleta wa able to observe it through X-rays, using primarily the XIS instrument on the Japanese Suzaku space telescope.

Urdampilleta and her colleagues compared their X-ray observations on shock fronts in the outskirts of Abell 3376 with radio measurements in that same region. In the periphery, shock fronts are usually associated with radio emissions either due to direct acceleration of electrons—called Diffusive Shock Acceleration—or due to re-acceleration of pre-existing cosmic ray electrons. The researchers conclude that at least in the case of the Western radio relic of Abell 3376, the electron acceleration mechanism seems to be consistent with Diffusive Shock Acceleration.

Publication

I. Urdampilleta, H.Akamatsu, F. Mernier, J. S. Kaastra, J. de Plaa, T. Ohashi, Y. Ishisaki, and H. Kawahara, ‘X-ray study of the double radio relic Abell 3376 with Suzaku’, Astronomy & Astrophysics