{lang en}

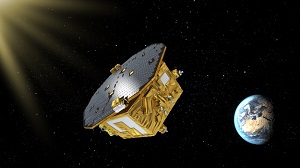

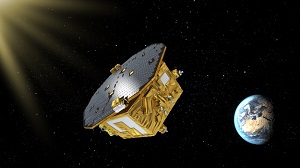

ESA’s LISA Pathfinder mission has demonstrated the technology needed to build a space-based gravitational wave observatory. Results from only two months of science operations show that the two cubes at the heart of the spacecraft are falling freely through space under the influence of gravity alone, unperturbed by other external forces, to a precision more than five times better than originally required.

In a paper published today in Physical Review Letters, the LISA Pathfinder team show that the test masses are almost motionless with respect to each other, with a relative acceleration lower than 1 part in ten millionths of a billionth of Earth’s gravity. The demonstration of the mission’s key technologies opens the door to the development of a large space observatory capable of detecting gravitational waves emanating from a wide range of exotic objects in the Universe.

Hypothesised by Albert Einstein a century ago, gravitational waves are oscillations in the fabric of spacetime, moving at the speed of light and caused by the acceleration of massive objects. They can be generated, for example, by supernovas, neutron star binaries spiralling around each other, and pairs of merging black holes. Even from these powerful objects, however, the fluctuations in spacetime are tiny by the time they arrive at Earth – smaller than 1 part in 100 billion billion.

LIGO

Sophisticated technologies are needed to register such minuscule changes, and gravitational waves were directly detected for the first time only in September 2015 by the ground-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). This experiment saw the characteristic signal of two black holes, each with some 30 times the mass of the Sun, spiralling towards one another in the final 0.3 seconds before they coalesced to form a single, more massive object.

The signals seen by LIGO have a frequency of around 100 Hz, but gravitational waves span a much broader spectrum. In particular, lower-frequency oscillations are produced by even more exotic events such as the mergers of supermassive black holes. With masses of millions to billions of times that of the Sun, these giant black holes sit at the centres of massive galaxies. When two galaxies collide, these black holes eventually coalesce, releasing vast amounts of energy in the form of gravitational waves throughout the merger process, and peaking in the last few minutes.

To detect these events and fully exploit the new field of gravitational astronomy, it is crucial to open access to gravitational waves at low frequencies between 0.1 mHz and 1 Hz. This requires measuring tiny fluctuations in distance between objects placed millions of kilometres apart, something that can only be achieved in space, where an observatory would also be free of the seismic, thermal and terrestrial gravity noises that limit ground-based detectors.

Key technologies

LISA Pathfinder was designed to demonstrate key technologies needed to build such an observatory. A crucial aspect is placing two test masses in freefall, monitoring their relative positions as they move under the effect of gravity alone. Even in space this is very difficult, as several forces, including the solar wind and pressure from sunlight, continually disturb the cubes and the spacecraft.

Thus, in LISA Pathfinder, a pair of identical, 2 kg, 46 mm gold–platinum cubes, 38 cm apart, fly, surrounded, but untouched, by a spacecraft whose job is to shield them from external influences, adjusting its position constantly to avoid hitting them. “LISA Pathfinder’s test masses are now still with respect to each other to an astonishing degree, ” says Alvaro Giménez, ESA’s Director of Science. “This is the level of control needed to enable the observation of low-frequency gravitational waves with a future space observatory.”

LPF experiments

LISA Pathfinder was launched on 3 December 2015, reaching its operational orbit roughly 1.5 million km from Earth towards the Sun in late January 2016. The mission started operations on 1 March, with scientists performing a series of experiments on the test masses to measure and control all of the different aspects at play, and determine how still the masses really are.

“The measurements have exceeded our most optimistic expectations,” says Paul McNamara, LISA Pathfinder Project Scientist. “We reached the level of precision originally required for LISA Pathfinder within the first day, and so we spent the following weeks improving the results a factor of five.”

These extraordinary results show that the control achieved over the test masses is essentially at the level required to implement a gravitational wave observatory in space. “Not only do we see the test masses as almost motionless, but we have identified, with unprecedented precision, most of the remaining tiny forces disturbing them,” explains Stefano Vitale of University of Trento and INFN, Italy, Principal Investigator of the LISA Technology Package, the mission’s core payload.

The first two months of data show that, in the frequency range between 60 mHz and 1 Hz, LISA Pathfinder’s precision is only limited by the sensing noise of the laser measurement system used to monitor the position and orientation of the cubes. “The performance of the laser instrument has already surpassed the level of precision required by a future gravitational-wave observatory by a factor of more than 100,” says Martin Hewitson, LISA Pathfinder Senior Scientist from Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics and Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany.

At lower frequencies of 1–60 mHz, control over the cubes is limited by gas molecules bouncing off them – a small number remain in the surrounding vacuum. This effect was seen reducing as more molecules were vented into space, and is expected to improve in the following months. “We have observed the performance steadily improving, day by day, since the start of the mission,” says William Weber, LISA Pathfinder Senior Scientist from University of Trento, Italy.

At even lower frequencies, below 1 mHz, the scientists measured a small centrifugal force acting on the cubes, from a combination of the shape of LISA Pathfinder’s orbit and to the effect of the noise in the signal of the startrackers used to orient it. While this force slightly disturbs the cubes’ motion in LISA Pathfinder, it would not be an issue for a future space observatory, in which each test mass would be housed in its own spacecraft, and linked to the others over millions of kilometres via lasers.

“At the precision reached by LISA Pathfinder, a full-scale gravitational wave observatory in space would be able to detect fluctuations caused by the mergers of supermassive black holes in galaxies anywhere in the Universe,” says Karsten Danzmann, director at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, director of the Institute for Gravitational Physics of Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany, and Co-Principal Investigator of the LISA Technology Package.

Today’s results demonstrate that LISA Pathfinder has proven the key technologies and paved the way for such an observatory, as the third ‘Large-class’ (L3) mission in ESA’s Cosmic Vision programme.

Notes for Editors

“Sub-femto-g free-fall for space-borne gravitational wave detectors: LISA Pathfinder results,” is published in Physical Review Letters The results were presented today during a media briefing at ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre in Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain.

Contributions

LISA Pathfinder is an ESA mission with important contributions from its member states and NASA. The LISA Technology Package payload has been delivered by several national funding agencies and ESA, in particular: Italy (ASI); Germany (DLR); the United Kingdom (UKSA); France (CNES); Spain (CDTI); Switzerland (SSO); and the Netherlands (SRON). LISA Pathfinder also carries the Disturbance Reduction System payload, provided by NASA-JPL.

Science operations involving the full LISA Technology Package will last until late June, followed by three months of operations with the Disturbance Reduction System.

{/lang} {lang nl}

De LISA Pathfinder-missie van de Europese ruimtevaartorganisatie ESA heeft met succes precisietechnologie getest voor het meten van zwaartekrachtsgolven vanuit de ruimte. De metingen van de afgelopen twee maanden tonen aan dat het technologische concept – met lasers heel nauwkeurig de variatie in de afstand meten tussen twee testblokjes die in vrije val door de ruimte reizen – de verwachtingen overtreft.

In een artikel dat vandaag verschijnt in Physical Review Letters, toont het team van LISA Pathfinder (LPF) aan dat de twee testblokjes ten opzichte van elkaar vrijwel niet bewegen. De gemeten onderlinge versnelling is minder dan een tienbiljardste van de zwaartekrachtsversnelling op aarde (g). De succesvolle test maakt de weg vrij voor de ontwikkeling van eLISA, een groot observatorium in de ruimte voor het waarnemen van zwaartekrachtsgolven, afkomstig van exotische objecten en verschijnselen in het heelal. eLISA gaat rond 2034 de ruimte in.

Het bestaan van zwaartekrachtsgolven werd 100 jaar geleden al voorspeld door Albert Einstein. Zwaartekrachtsgolven zijn rimpelingen in het weefsel van de ruimtetijd, die met de snelheid van het licht reizen en ontstaan door de versnelling van extreem zware objecten. Ze kunnen worden veroorzaakt door kosmische verschijnselen als supernova’s, neutronendubbelsterren die om elkaar heen draaien en samensmeltende zwarte gaten. Maar zelfs deze extreem energierijke verschijnselen brengen maar zeer geringe rimpelingen in de ruimtetijd teweeg. Tegen de tijd dat ze de Aarde bereiken verstoren de golven de ruimtetijd met minder dan een triljoenste procent.

Om zulke minieme rimpelingen toch te kunnen waarnemen hebben wetenschappers zeer geavanceerde technologieën nodig. Zwaartekrachtsgolven werden pas in september 2015 voor het eerst ontdekt door de LIGO-detector in de VS. Het LIGO-Virgo samenwerkingsverband zag een signaal van twee zwarte gaten, van respectievelijk 29 en 36 zonsmassa’s, die samensmolten en een nieuw zwart gat van 62 zonsmassa’s vormden. In de laatste 0,3 seconde voor de samensmelting werden 3 zonsmassa’s omgezet in de zwaartekrachtsgolven die door LIGO werden geregistreerd

De signalen die LIGO opving, hadden een frequentie van ongeveer 100 Hz. Maar zwaartekrachtsgolven bestrijken een veel breder spectrum. Met name laagfrequente trillingen worden veroorzaakt door exotische verschijnselen als het samensmelten van twee superzware gaten. We vinden deze superzware gaten, die een massa hebben van miljoenen tot miljarden keren de massa van de zon, in het centrum van sterrenstelsels. Wanneer twee sterrenstelsels botsen, smelten de twee zwarte gaten in het centrum gaandeweg samen. Tijdens de samensmelting produceren ze enorm veel energie in de vorm van zwaartekrachtsgolven, met een piek in de laatste paar minuten voor de definitieve samensmelting.

“eLISA geeft echt weer hele nieuwe kansen om fundamentele natuurkunde te bestuderen en om het ontstaan van structuur in het heelal te volgen,” zegt Gijs Nelemans van de Radboud Universiteit en leider van het Nederlandse eLISA consortium.

Om deze verschijnselen waar te nemen en volop gebruik te maken van het nieuwe venster op het heelal dat de zwaartekrachtsgolven bieden, is het cruciaal om zwaartekrachtsgolven met een lage frequentie (0,1 mHz-1 Hz) te meten. Dat betekent: minieme fluctuaties meten tussen objecten die zich miljoenen kilometers van elkaar bevinden. Dit kan alleen in de ruimte, met een observatorium dat geen last heeft van seismische en thermische verstoringen op aarde noch van de zwaartekrachtsruis van de aarde zelf. Detectoren op de grond hebben hier wel last van.

Sleuteltechnologie

LISA Pathfinder is ontworpen om de sleuteltechnologie voor een ruimteobservatorium te testen (eLISA). Een cruciaal onderdeel van de test is het met lasers continue meten van de positie van twee testblokjes die in vrije val, alleen onder invloed van de zwaartekracht, door de ruimte bewegen. Dat is zelfs in de ruimte extreem moeilijk omdat er allerlei factoren zijn – zoals de zonnewind en de druk van het zonlicht – die een verstorende werking hebben. Daarom heeft LISA Pathfinder twee identieke goud-platina blokjes (2 kg, 46 mm) aan boord, die op een afstand van 38 cm van elkaar door de ruimte vliegen, omgeven door maar niet in contact met het ruimtevaartuig dat de blokjes afschermt. Met lasers, bundelsplitsers en een reeks kleine spiegeltjes wordt heel nauwkeurig, tot bijna op atomair niveau, variaties in de afstand tussen de blokjes gemeten.

LISA Pathfinder werd 3 december 2015 gelanceerd en bereikte eind januari 2016 zijn beoogde positie, ongeveer 1,5 miljoen km van de aarde in de richting van de zon. De experimenten begonnen op 1 maart. “De metingen hebben onze meest optimistische verwachtingen ruimschoots overtroffen,” zegt Martijn Smit, die de SRON-bijdrage aan LPF coördineert. “Het LPF-team bereikte al op de eerste dag de benodigde precisie en in de weken daarna werd dit nog met een factor vijf overtroffen. Dat is echt een ongelooflijk knap resultaat en een mooi staaltje precisietechnologie.”

Nederland

Nederlandse ingenieurs, natuurkundigen en sterrenkundigen zijn nauw betrokken bij beide missies. Ruimteonderzoeksinstituut SRON heeft in de aanloop naar de lancering testapparatuur ontwikkeld voor LISA Pathfinder. TNO heeft verschillende systemen getest en ontwikkeld, waaronder een systeem dat ervoor zorgt dat de laserbundels van eLISA exact op de goede plek terechtkomen. Zelfs over een afstand van 1 miljoen km. Voor eLISA bundelen Nikhef, de Radboud Universiteit, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Universiteit Leiden, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Universiteit Twente, de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam en SRON de krachten op wetenschappelijk gebied. Nikhef, TNO, NOVA en SRON werken samen in de technologieontwikkeling voor eLISA.

Publicatie

De resultaten van het onderzoek zijn gepubliceerd in een artikel in Physical Review Letters, onder de titel Sub-femto-g free-fall for space-borne gravitational wave detectors: LISA Pathfinder results. De resultaten zijn vandaag gepresenteerd op een persconferentie bij het European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC) in Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spanje.Om 14.00 uur vindt er een ‘Ask Me Anything’ sessie plaats via Reddit.

{/lang}